Ah, beautiful West Texas: A vast desert land with mountains, the mighty Rio Grande, and incredible ecosystems that thrive in this desolate region of the Lone Star State. Whether you are making a long road trip or just visiting from El Paso, Big Bend National Park is a genuine sight that will remind you of the incredible feats of the natural world.

Before we jump into what is now known as Big Bend National Park, let us first acknowledge that these lands belong to the Jumanos, Kónits?...?...íí gokíyaa (Cúelcahén Ndé - Lipan Apache), Coahuiltecan, Mescalero Apache, and Chiso Native tribes. Click each link to learn about these Native tribes and how you can support their call for freedom.

About the Land at Big Bend National Park

Nestled alongside the Rio Grande River and the border of Mexico in the Chisos Mountains of West Texas, Big Bend National Park is truly a sight to behold. Complete with intimidating canyons, desert vistas, forested peaks, and a powerful river, Big Bend N.P. features a vibrant escape near the Terlingua. The National Park Service (NPS) acquired the sacred lands of the Chisos Basin from Texas in a deed to the Federal Government in 1943, and the park was officially established in 1944.

Amazing Features of the Park

Big Bend National Park boasts 150 miles of dirt roads, 100 miles of paved roads, and almost 200 miles of amazing hiking trails. Enjoy a scenic drive, hike, take a backpacking trip, horseback ride, visit the Hot Springs Historic area, or float the Rio Grande River.

One of the best things to do is to drive along the Ross Maxwell Scenic Drive and take in glorious views of the Chihuahuan Desert, ending at the banks of the Rio Grande. Another park highlight is situated 8 miles north of Panther Junction at the award-winning Fossil Discovery Exhibit.

Hiking Trails at Big Bend

Hikers visit from far and wide to discover the miraculous scenery and trails found at Big Bend. The hikes. Take a quick stroll to Santa Elena Canyon, the famous 1.4-mile round trip leading to breathtaking vistas.

The Window View Trail is a quick 0.3-mile walk through the forest in the Chisos Mountains, while the Lost Mine Trail (5 miles round trip) presents even more alpine vistas. If you have more time to spare in the park, the Window Trail offers a 6-mile round trip hike in the Chisos Basin.

The Chihuahuan Desert Nature Trail is a great option for birdwatchers, and the Rio Grande Village Visitor Center features historical exhibits about the river. Take the Boquillas Canyon Trail to the entrance of a magnificent canyon and, if you have a passport, pay a quick visit to the small Mexican village of Boquillas del Carmen.

The Chisos Mountain Trails area hikes are widely loved and include fun adventures such as Emory Peak, Boot Canyon, and South Rim. For those who really want time in the woods, purchase a backcountry campsite permit and spend a few nights backpacking at the Laguna Meadows campsites.

The Grapevine Hills Trail (2.2 miles round trip) offers access to a widely-photographed group of balanced rock that is an exciting sight to witness. For a longer, more remote trek, take the challenging Mariscal Canyon Rim Trail (6.5 miles round trip) into the western flanks of Mariscal Mountain. Do not do this hike in warmer months.

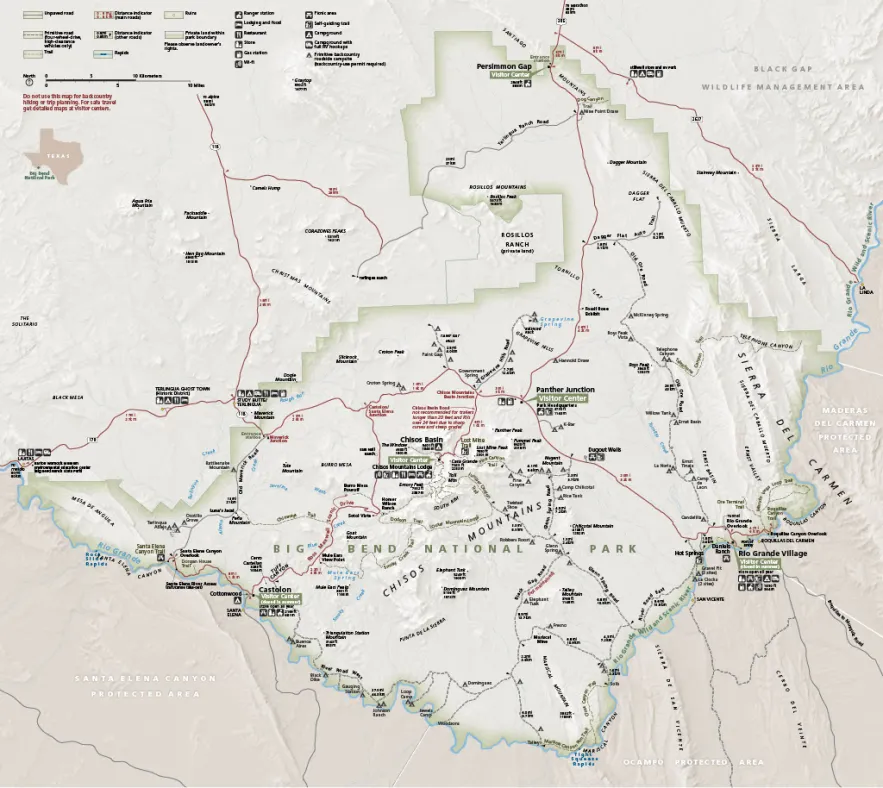

Big Bend National Park Map

For all kinds of helpful maps, including topographic maps of Big Bend National Park, this site features all sorts of interesting maps, including night sky maps, vegetation maps, trailhead maps, lodging maps, historical maps, and so many more!

Camping at the Park

RELATED: Redwood National and State Parks Guard California's Coastline

The National Park Service manages four campgrounds at the park, including three developed sites in the front country and one full RV hookup site managed by Forever Resorts. There is the Chisos Basin Campground (NPS run, 60 sites), the Rio Grande Village Campground (NPS run, 100 sites), Cottonwood Campground (NPS run, 24 sites), and the Rio Grande Village RV Park (operated by Forever Resorts. 25 sites with full hook-ups).

Important Information

The peak season for visiting Big Bend is usually between November and April. It is highly recommended to make reservations for camping and lodging as early as possible to ensure you have somewhere to stay.

Entrance fees for the park range in price depending on what type of car you arrive in, how big your group is, and how long you are visiting. Check here for information on closures and current costs.

There are five visitor centers within Big Bend National Park, including Panther Junction, Rio Grande Village, Castolon, Persimmon Gap, and the Chisos Basin. Each offers various evening programs, talks, guided tour options, special events, and park rangers to talk to about important questions you may have.

Nearby Attractions

While you are in the area, be sure to visit Guadalupe Mountains National Park, Big Bend Ranch State Park, and stop in Marathon for lunch!

Frequenter of Big Bend National Park? Share your expert tips at our Wide Open Roads Facebook!